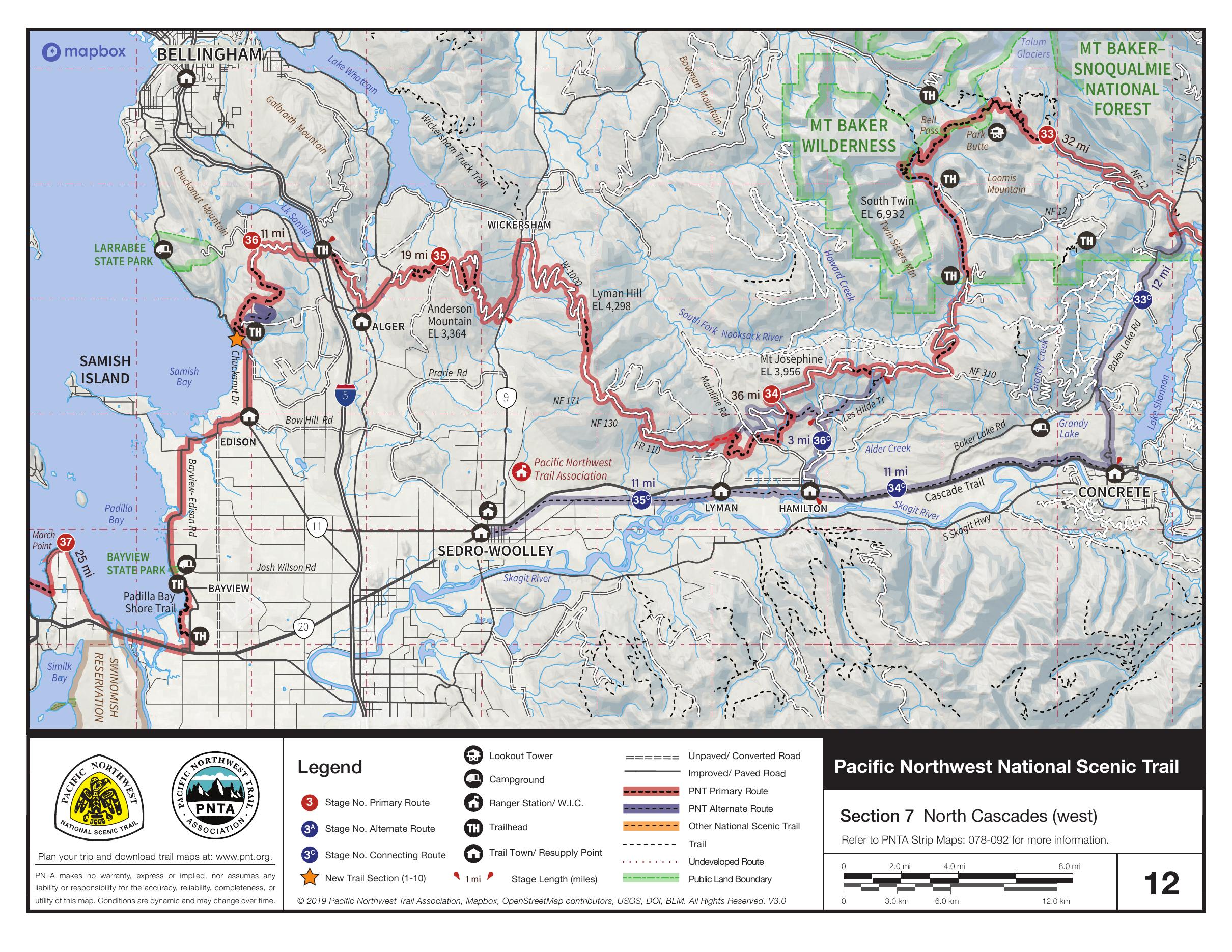

Park Butte

I chatted with Moose the next morning outside of his room. He and Bugs had decided to walk the unofficial rail-trail alternate route to Sedro-Wooley instead of winding through endless logging roads on the PNT route. I’d probably take a while to catch up, so I gave him a hug goodbye and told him to say goodbye to Bugs for me.

I did take the rail trail a couple miles downtown to get to the road where I’d hitch a ride. It was a wide, flat crushed-limestone path lined with sugary-sweet blackberries. I could see the appeal, but the purist in me needed to see what the official route was like.

It took a long time to get a hitch – I spent about 2 hours walking along the non-existent shoulder of that windy, fern-lined car advertisement road that I’d come into town on with Bugs and Moose. I waited probably 15 minutes between car passings. But I eventually got picked up by a strangely-untalkative older guy in an old red sedan. He dropped me off at my next stop on the PNT, an old forest road that you would never notice if you were driving past it.

I trudged up the forest road for about an hour. As I ascended, the hard-pack gravel surface was slowly replaced by moss, ferns, and small shrubs. I passed a number of small ancient-looking water tanks hidden in the forest that must have at some point supplied water to the towns below.

That forest road abruptly joined a much more well-traveled one. I got passed by a few cars before one slowed down beside me and asked if I wanted a ride up to the trailhead. Who am I to decline such an offer? I climbed in the backseat after shoving aside a mountain of gear. The two women in the front seats were old college friends who were taking a camping trip together. We didn’t have much time to talk since the trailhead was only a couple of miles ahead.

We passed Marguerite and Rebecca, the PNT hikers I’d met briefly in Oroville, on the way up the hill. They couldn’t fit in the car on account of all the camping gear, but they asked if I could save a spot for them in the Park Butte fire tower if I got there first.

It was easy to see why the Park Butte trail was so well-travelled. It was a

beautiful, misty, forested climb to a sudden clearing with Mount Baker looming

ahead larger than ever. I loaded up on water at a small stream (W839) and

continued my climb at a slow pace. Before long, I caught a glimpse of the fire

tower, perched precariously on the top of a jagged hill, just before I caught

the side trail.

A thick stratus cloud layer started converging probably not more than 200 feet above my head as I made the climb up to Park Butte. Mount Baker was gone, replaced with a dull white-grey sheet. The trail wound through sharp ridges covered in low brush, ascending to the rocky Park Butte summit. I was glad to make it to the fire tower, but slightly dismayed when I saw that it was already claimed for the night by a family of three – a dad and his two kids.

The family was really cool, though. The dad encouraged me to hang out and we talked for quite a while about hiking while watching Mount Baker fade in and out of the fog. He had climbed Mount Baker the previous year, ascending in the early morning hours (most climbers do this to avoid the hazard of melting ice in the sunlight). He told me that if we got lucky overnight, we may be able to see the glow of headlamps crawling up the glacier. The kids were between 6 and 10, and they were extremely outgoing and inquisitive.

I left the fire tower to answer a call of nature. On the way to the patch of trees where I dug my cat-hole, I found a somewhat-flat tent site just below an exposed knife-edge ridge and decided to set up camp there. I knew it would be cold, but I thought the views might be worth it, and they certainly were. I ate a dinner of mashed potatoes in front of the mountain’s flamboyant evening cloud dance.